“People Don’t Want to Be Managed, They Want to Be Unleashed”

The Humanitarian HR Asia conference this month in Kuala Lumpur is asking questions about Talent Preparedness and Humanitarian Leadership. To me, the combination of Leadership with Talent in the title is key, and rightly extends the agenda from HR to leadership and the whole organisation.

The Humanitarian HR Asia conference this month in Kuala Lumpur is asking questions about Talent Preparedness and Humanitarian Leadership. To me, the combination of Leadership with Talent in the title is key, and rightly extends the agenda from HR to leadership and the whole organisation.

Jonathan Potter stresses in chapter 11 of ‘On the Road to Istanbul’[1] that “Competent and well-managed staff are at the heart of an accountable and effective organisation.” Hard to argue with, but also sometimes hard to achieve.

‘Well-managed’?

Respondents to Roffey Park’s annual Management Agenda survey in 2015[2] identified ‘Developing appropriate leadership and management styles’ as the number one people challenge (86%) their organisations were facing. Across all sectors, respondents said that the missing quality was ‘empowering staff’. But ‘empowerment’ and motivation aren’t something leaders can give. As Niels Pflaeging puts it, “The truth is: because of motivation’s intrinsic nature, leaders, through their behaviour, can only demotivate, or at best create the context for motivation to show up.”[3] But how?

As Humanitarian organisations face increasingly unpredictable and ambiguous challenges, the need is for leadership and cultures that fit. No longer can we pretend our organisations are like machines, and humans only ‘resources’. Instead we need to be at home with the reality that our organisations are complex dynamic human systems, with their own unpredictability and ambiguity, and create cultures which sustain effectiveness and allow people to flourish.

A culture for effectiveness

The second most common ‘people challenge’ identified by respondents in our study, across all sectors, was “Employee engagement and morale”(72%).

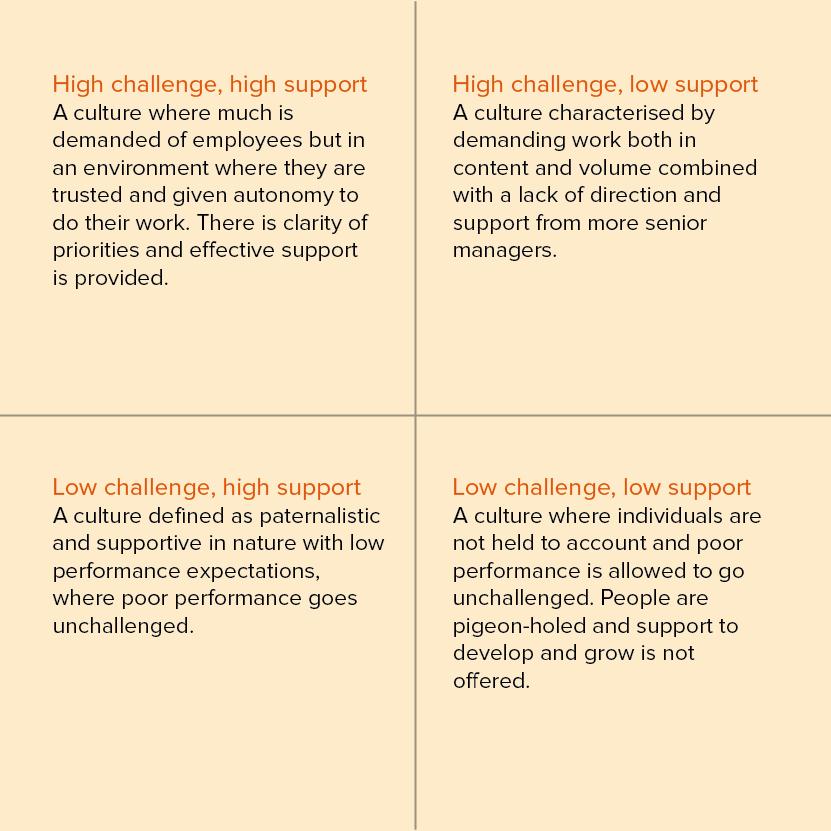

So we asked people a question: ‘describe your organisational culture in terms of support and challenge’.

The results were striking, and polarised.

In the private sector, it was encouraging to find 42% of respondents characterising their culture as ‘High Support / High Challenge’. However, in the public sector this fell to only 27%, and 45% described it as ‘High Challenge / Low Support’. In other words, a culture which drives otherwise motivated people to burnout and disengagement. It might be worth you asking the same question of your organisation?

So how does a High Support / High Challenge culture help make the best of, and grow talent? Countless studies (e.g. Dan Pink[4]) have confirmed that what inclines us humans towards engagement and effectiveness involves a combination of:

- Competence,

- Autonomy,

- Purpose, and

- Relatedness.

Competence – being able to do what we do well, feel we are getting better at it, and be supported in growing our capability and skill. This combines both appreciation and development.

From our own study, ‘Poor management’ and ‘Lack of appreciation’ were found to be among the top three reasons people gave for planning to leave their organisations.[5] The good news is that research (e.g. David Rock[6]) suggests when people feel they are learning and improving, particularly if that’s acknowledged and valued by their managers, especially publicly, it contributes hugely to engagement and motivation, also meeting a basic human need for status.

So how effective are the leaders in your organisation at enhancing people’s sense of competence?

What about Autonomy?

“When people solve things themselves, the brain makes patterns and emits a rush of dopamine”. [7]

If engagement and effectiveness are enhanced by people having a sense of autonomy, what conditions must leaders create in order to maximise the chances of people acting autonomously? It takes a culture of trust, of curiosity, willingness to experiment and freedom to fail. Organisations which treat their people as ‘owners’ more than ‘employees’, as capable decision makers, as responsible adults, prove this day in, day out.

How’s your culture on that? And how well do your leaders encourage autonomy?

Purpose?

Surely this one is a given? People work in the humanitarian sector for its purpose. True. But what about their particular day to day role? How clear are people about the line of sight between their job and the big picture?

What about Relatedness?

As Dave Ulrich recently emphasised[8], HR must be about relationships. Jonathan’s chapter[9] also highlighted the importance of ‘connection’, of ‘communication’ especially in matrix working. Research continues to confirm our human need for connection and inclusion, and the damaging effect of disconnection and exclusion. So to address this, Parsons and Brown[10] raise the challenge that “Leadership styles must move from command and control to collaboration.” But again it requires trust to flow from the top down.

So in your own organisation, if you’re going to make the best of the talent available to you, how relational is your culture, and how collaborative and connected do people feel?

So what?

It’s not surprising Jonathan stressed what he did in chapter 11. This was at the heart of People In Aid’s mission for over 15 years. But as humanitarian organisations, our talent agenda has to go beyond HR. If we are to continue meeting the challenges we face, continue being organisations people want to join to invest their talent, imagination and energy, then the talent agenda is a leadership agenda. And the leadership agenda must be about creating and sustaining cultures characterised by high support as well as high challenge. And, if we act on the neuroscience, ‘well-managed’ includes recognising the importance of competence, autonomy, purpose and relatedness. Why? Because “…people don’t want to be managed, they want to be unleashed.”[11]

[1] On the road to Istanbul: How can the World Humanitarian Summit make humanitarian response more. effective?’ CHS Alliance; (2015) Jonathan Potter, Chapter 11, ‘People Management: the shape of things to come’.

[3] “Organize for Complexity”. (2014) Niels Pflaeging (p19).

[4] Pink, Daniel H (2009) ‘The surprising truth about what motivates us.’ Riverhead Books, 375 Hudson St, New York, NY, 10014-3672.

[5] The Management Agenda (2015) Roffey Park.

[6] Rock, D, (2007) ‘SCARF: a brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others’. NeuroLeadership Journal. Issue One.

[7] “The brain and Organizational Performance”. (2014) James Parsons & Prof. Paul Brown.(p11) www.iedp.com

[8] ‘The future of HR is about relationships – People Management Magazine online 24 March 2015.

[9] On the road to Istanbul: How can the World Humanitarian Summit make humanitarian response more effective?’ CHS Alliance; (2015) Jonathan Potter, Chapter 11, ‘People Management: the shape of things to come’.

[10] “The brain and Organizational Performance”. (2014) James Parsons & Prof. Paul Brown.(p11) www.iedp.com

[11] “The brain and Organizational Performance”. (2014) James Parsons & Prof. Paul Brown.(p7) www.iedp.com

Read more about people management in the 2015 Humanitarian Accountability Report at: https://www.chsalliance.org/resources/publications/good-people-management