Facing the facts of where we are at: internal global review highlighting obstacles and opportunities for the Danish Refugee Council to address Commitment 5 of the CHS

Danish Refugee Council (DRC) country offices have, where possible, implemented Feedback and Complaint Response Mechanisms (FCRMs) that are context-specific and reflect the demands as well as the capacities on the ground. This has generated field-level learning; however, this is not available to the organisation as a whole. Therefore, to understand DRC’s current standing and engagement with community FCRM’s, a learning synthesis and global review was undertaken to systematically collect and collate the different experiences and practices of DRC country offices on the design, implementation and management of FCRM’s. The project generated a report with global takeaways, lessons learned and success stories meaning that the organisation has a better understanding of current practice of FCRMs within DRC globally.

The summary of findings are available in a short-form Learning Brief highlighting the 10 key “obstacles and opportunities” to implement effective FCRM systems in current DRC practice. These findings feed into the finalisation of DRC global FCRM guidelines. With support of the CHS Alliance, the learnings have been disseminated internally, and externally.

The what (purpose)?

Overall, the review aimed to improve DRC’s inter-country learning and compliance with Commitment 5 of the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS). Specifically, to:

- conduct a global review of DRC’s common standards, best practices and diverse approaches to establishing community FCRM’s in country operations.

- produce a systematic learning synthesis for use by DRC staff across the organisation, drawing out commonalities and differences, and summarising case examples of contextually diverse FCRM’s to support mainstreaming of appropriate and effective participation and accountability practices.

- develop a global repository of country office FCRM documentation with global access to improve inter-country learning, access to FCRM materials and increase knowledge retention beyond the individual.

- establish DRC’s first Global Accountability Working Group where colleagues can connect, request support and share tools, ideas, relevant events and resources.

The why?

The decentralised nature of DRC lends itself to flexible and varied processes depending on the context and set-up of specific country offices. This has its benefits, for there is no ‘one-size’ fits all approach when it comes to a successful FCRM, however, DRC and its country offices would benefit from a more structured and streamlined approach when it comes to the design, implementation and maintenance of FCRM’s. Further, despite strong ambitions, for DRC the lack of engagement with displacement-affected people came to light during the CHS certification compliance audits (2017 and 2019), where independent accredited auditors repeatedly highlighted areas of non-conformity to Commitment 5 of the CHS on complaints handling systems. Accordingly, reviewing the obstacles and opportunities outlined as a result of this exercise is a good starting point for DRC country offices in rectifying some of the widespread weaknesses documented in regard to this Commitment.

The how?

First a literature review was conducted to present current thinking and knowledge within the sector regarding FCRMs and current principles, standards and guidelines. Following this, selection criteria were developed based on the literature review to identify best practice, which were used to analyse the DRC internal FCRM documentation and systems in place. The third stage entailed a call-out to DRC country offices to request all of their FCRM documentation. These documents have been collated in a global repository now available to the organisation as a result of this exercise. Of the country offices that participated in this review, five were selected for follow-up with semi-structured qualitative interviews in which questions were asked about the country offices’ specific FCRM contexts, challenges and lessons learned. Finally, an analysis and write-up of the findings was undertaken. It was decided that the final product would take the form of both a long-form report (for internal purposes) and a short-form learning brief extracting the essential findings for wider sharing.

Overview of main takeaways

Of the country offices reviewed, many have sound and satisfactory systems in place, but none are perfect, and all could benefit from a greater investment of resources and significant improvements to systemisation. Establishing FCRM systems is an incredibly fastidious process – requiring extremely detailed and clear structures, systems and staffing to manage feedback, not to mention extensive engagement and involvement with communities as much as feasible at the field level. The key areas highlighted for DRC as requiring the most significant room for improvement are outlined in the Learning Brief as the 10 key obstacles, they are:

- Community participation is overlooked – of particular note is the lack of emphasis placed on engagement with communities at the field level – we must first understand our communities and context and always seek to involve them in FCRM design and decision-making processes at all stages.DRC can prioritise spending time with communities, building trust and relationships and embedding opportunities in the project cycle to routinely listen and promote participation. Failing to do so can undermine the rights of the people we aim to serve, as well as the overall quality and efficacy of our interventions.

- Feedback and complaint categories are ambiguous – without explicit criteria outlining the specifics of each category, the system will likely be inefficient, and the resolution of cases will be slowed, which ultimately undermines the entire system and has the potential to cause harm to affected populations.

- Complaints handling procedures lack clarity and simplicity – details matter: all systems, structures and staff roles and responsibilities must be carefully planned for and documented. All procedures should be clearly and simply laid out, leaving no room for ambiguity. All parts of the feedback loop cycle should be straight-forward both in terms of instruction and actions.

- Lack of adequate triaging and linkages between programmatic and sensitive complaints – of particular concern was the disconnect between the FCRMs and DRC’s global Code of Conduct Reporting Mechanism in most country offices. The two systems are inherently linked and it is of utmost importance that the systems are set up to ‘talk’ to each other, and more specifically that staff are trained in the handling of all complaints, especially sensitive cases, and how and where to direct them.

- Definitive and clear-cut timeframes for resolution are needed – many DRC country office FCRM procedures reviewed did not clearly outline the response and closure times for each feedback or complaint category. If communities are not being responded to in a timely manner, then they will doubt the efficacy of the system and will not use it.

- Inadequate prioritisation of staff training and role delineation – FCRM’s require the necessary human resources and investing in appropriate training: it is integral for any system that key staff who are involved in the running of the mechanism, at all levels, are well trained and their duties are clearly identified in system documents so that everyone knows who to go to at each stage of the feedback follow-up process.

- Information management safeguarding procedures are not in place or transparent – clear processes and controls need to be implemented to ensure only authorized staff have access to FCRM data and that sensitive feedback is managed appropriately.

- Significant oversight of informed consent – asking for and gaining informed consent at the time the feedback was provided through to referral processes was thoroughly under stressed in the DRC documents reviewed.

- Ineffective communication, promotion and awareness raising of all aspects of the FCRM – it is critical to communicate clearly: a) what a complaint mechanism is as well as its purpose; b) how it can be used; and c) how feedback raised will be managed, followed-up and within which timeframes.

- Knowledge loss between country offices – DRC’s decentralized nature means that often there is a lack of communication and knowledge sharing between country offices and part of the reason this review came about.

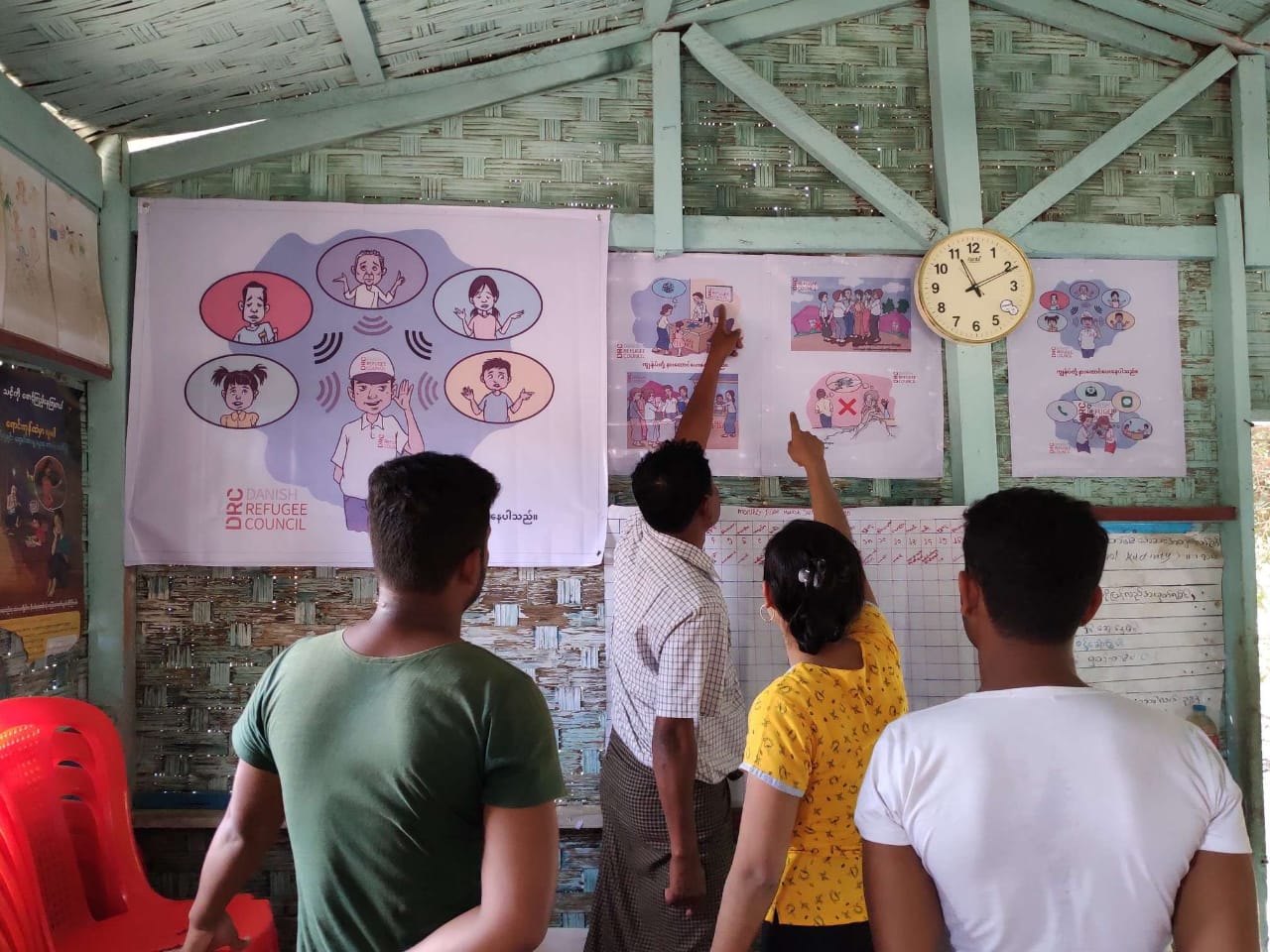

Whilst the obstacles set out above outline the main shortcomings of DRC’s FCRMs, they are not intended to overlook the solid work that country offices are doing, often in very difficult contexts and always with limited resources. There is much to be proud of and there is a strong foundation from which DRC can learn and improve. DRC can be proud of the innovative CRM mobile response teams in Myanmar, the widely used hotline in Somalia, and the collaboration with numerous agencies in Uganda to name but a few. DRC does not have to reinvent the wheel but merely build on what is already in place.

We can and must do better

The weaknesses regarding FCRMs are not unique to DRC, this is a sector-wide challenge, as outlined by the CHS Alliance and their review of the CHS commitments, where Commitment 5 consistently scores the lowest amongst organisations audited against the Standard. There have been great steps taken over the last decade to improve this sector-wide failing, but much more needs to be done. If humanitarian and development organisations do not make room for and embed FCRM’s into the core essence of their work and programming, they run the risk of doing harm, and delivering projects which are ineffective and waste much time, money and resources.

Providing a formalised structure to take into account the views, opinions, concerns, suggestions and complaints of affected populations is fundamentally about basic respect: providing an avenue for dialogue, participation and prioritising our duty to honour stated commitments and humanitarian principles. FCRM’s are an effective and tangible way to be accountable to the people and communities we aim to assist. Managers and senior staff in particular should promote a culture where feedback and complaints are welcomed and addressed – their support for the implementation of FCRM systems is vital.

Crucially, when effectively implemented, FCRM systems act as a marker as to how well humanitarian actors are faring in meeting all other commitments of the CHS. They can indicate the impact and appropriateness of an intervention, potential risks, vulnerabilities and opportunities – as well as the degree to which a response is well-coordinated, and the satisfaction levels of the services provided. Ultimately it is hoped that this project is the beginning of improvements to DRC’s inter-country operational learning and compliance with Commitment 5 of the Core Humanitarian Standard.

Findings are available in a short-form Learning Brief. To find out more about the project, join Joanna and Charlotte at their session at the virtual Global CHS Exchange 2020 6-8 October.