“It’s about justice and dignity”: Breaking the Silence on sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in Bangladesh

To tackle sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment, data is vital — yet communities and local NGOs often face barriers to joining schemes like the Harmonised Reporting Scheme. In this article, civil-rights-lawyer-turned-humanitarian Syed Rashed Bin Jamal shares his journey and how he helped organisations in Cox’s Bazar participate, enabling accurate data, trend analysis and stronger safeguarding rooted in local realities.

For years, dedicated individuals and organisations across Bangladesh have worked to build safeguarding systems to protect communities from sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment (SEAH). Formal mechanisms were established, trainings delivered, and coordination platforms developed.

Yet, despite these important foundations, challenges remained – particularly when it came to trust, access, and accountability to survivors. In a project on participatory action research by BRAC University, it became apparent that reporting rates were low, systems were underused or misunderstood, and survivors often felt silenced by processes that weren’t built with their lived realities in mind.

Recognising this, the CHS Alliance launched the Closing the Accountability Gap project in Cox’s Bazar in 2023. Led by Syed Rashed Bin Jamal, the CHS Alliance Liaison Officer based in Cox’s Bazar, the initiative aimed to complement and strengthen existing efforts by taking a survivor-centred, community-informed approach to PSEAH.

“There was already a lot of good work being done,” Rashed explains. “But what we saw was that the people most affected by SEAH, especially survivors, weren’t always at the heart of the systems designed to protect them.”

Syed Rashed Bin Jamal, CHS Alliance Liaison Officer based in Cox’s Bazar

From Law to Local Leadership

For Rashed, this work was deeply personal. A trained civil rights lawyer, Rashed transitioned into humanitarian protection after years working with the garment industry – working with unions, on women’s rights and on children’s rights.

After the Rohingya refugee crisis in 2017, when he supported the PSEAH Network in Cox’s Bazar, he saw both the scale of the problem and the limitations of traditional responses.

Listening to the Community

One of the most striking findings was that 89% of SEAH disclosures were not going through formal channels, but instead being shared with community figures – local leaders, imams, women’s representatives – who survivors trusted more than official reporting systems.

“There were barriers everywhere including confidentiality concerns, delays, fear of retaliation or shame,” he says. “So people turned to those they trusted.”

“These people were already receiving disclosures. We could either ignore that reality, or we could find ways to work with them – and train them – so survivors didn’t fall through the cracks.”

A participant speaks at a workshop on locally-led victim-centred approaches to PSEAH in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, May 2024. Credit: CHS Alliance

Rashid mapped, trained, and supported these informal actors – helping them understand confidentiality, referral pathways, and survivor rights – so they could safely connect survivors to formal services.

This approach faced some early resistance. Larger actors expressed valid concerns about confidentiality and data protection. But over time, trust was built and progress made.

“This was about more than policies—it was about shifting power. We had to help organisations see that being accountable means putting survivors’ rights above institutional image. We weren’t asking organisations to give up their standards, we were asking them to see that survivors were already speaking – but just not through the channels they had expected. It became about building trust in both directions.”

Kutupalong refugee camp, Cox’s Bazar, credit: Medair

Data That Drives Change

This work laid the foundation for the next phase: supporting organisations to participate in the CHS Alliance Harmonised Reporting Scheme (HRS) in Bangladesh – a scheme which enables organisations to submit anonymised SEAH data into a secure global platform in order to produce real-time, country-specific trend analyses.

Using a self-assessment tool based on global best practices, Rashed trained and mentored each organisation to identify areas for improvement – whether in policies, reporting pathways, survivor-centered support, or organisational culture.

“It wasn’t just training,” says Rashid. “It was accompaniment. It was about helping organisations walk the talk – so that safeguarding becomes part of who they are, not just what they say.”

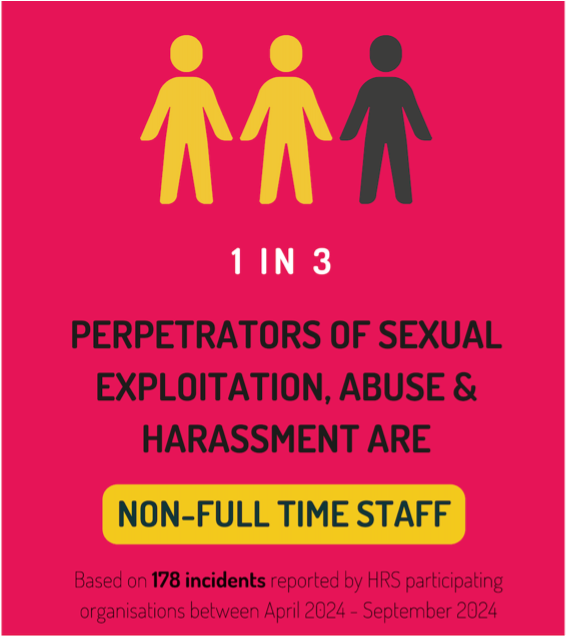

1 in 3 of SEAH perpetrators are non-full time staff

“We didn’t make HRS membership mandatory, but over 90% of those we mentored joined. For the first time, they had real data that showed what was happening in their own operations. They could see patterns. They used that data to talk to donors, adjust programmes, and improve safeguarding. HRS gave them trend analysis, like the role of middle management as perpetrators.”

Organisations reported a shift in internal culture and HRS data being used strengthen dialogue with donors.

“For the first time, organisations were saying: ‘We have data that actually reflects what’s happening’, says Rashid “That’s a huge shift – from guessing to knowing.”

Where from here?

The interest in HRS continues to grow. Local NGOs are asking to join. UN agencies are exploring how the platform could strengthen their own partner monitoring. And Bangladesh’s PSEAH networks are encouraging more widespread adoption.

With funding cycles shifting and global attention often pulled elsewhere, safeguarding efforts can sometimes fall by the wayside. But the work in Bangladesh shows that meaningful, community-driven, data-informed change is possible – and that it can be done in ways that honour both global standards and local realities.

“It’s not about choosing between formality and informality,” Rashid says. “It’s about making sure the system works – because when it doesn’t, it’s the survivors who pay the price.”

“I will continue to help survivors navigate injustice, help organisations to be accountable. It’s about justice. It’s about dignity. And it’s about standing with those who’ve been harmed and making sure they’re not alone.”

Find out more and join the Harmonised Reporting Scheme to play your part in a safer, more accountable aid system.